By Dr Tristan Jenkinson

Introduction

In my talks on ChatGPT and (Generative AI in general) I have regularly raised the point that OpenAI (the owners of ChatGPT) have provided little information on the specific data sets that were used to train their models for ChatGPT. One issue with this is that with little understanding of the data within the model, it is very difficult to understand what biases may exist in the training data, and hence identify potential mitigation strategies to address them. This is point that I cover in a previous article.

One of the other key issues linked to the OpenAI training data is that many people believe that their data has been used to train the ChatGPT models without their consent, and were never offered payment for the use of their data in training the GPT models. The value in using ChatGPT comes from the power of its models, which would be nothing without the data that they have been trained upon. One reason that some consider this particularly concerning is that, based on those models, OpenAI is currently valued at an eye-watering $157 billion.

Copyright Complications

The issue gets more complicated with copyright data, with holders of copyright data obviously concerned that their protected content is being misused.

To provide examples, researchers at Stanford University (in the paper Foundation Models and Fair Use) found that:

- They could extract the entirety of “Oh the Places You’ll Go!” by Dr. Seuss verbatim using GPT4

- Using GPT 3.5 (reported as “ChatGPT” but they appear to be referring to GPT3.5) they were able to extract the first three pages of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone verbatim before there was divergence.

- Using GPT 4, attempts to extract text from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone directly, swiftly failed.

- Using GPT 4 and an approach which replaced the letter ‘a’ with the character ‘4’ and every ‘o’ with a character ‘0’, they were able to extract the first three and a half chapters (not pages) verbatim.

A further research paper (Trustworthy LLMs) can be found on AI resource and platform Hugging Face. Page 36 of the PDF file details some of the tests regarding copyright content leakage.

OpenAI admitted in January last year that their models could not work without the inclusion of copyrighted content.

Even today (30 January 2025), ChatGPT itself will explain that it is trained on copyrighted materials. Using the prompt “Are there specific examples where ChatGPT has been shown to return content which is taken from copyrighted material” the response begins:

“Yes, there have been discussions and concerns regarding AI models, including ChatGPT, generating content that might inadvertently resemble or derive from copyrighted materials. This is largely because these models are trained on vast datasets that include a wide array of internet texts, books, articles, and other media, some of which are copyrighted.”

Interestingly, unlike other chats which are automatically labelled with relevant titles to browse through, this request is simply labelled “New chat”.

The argument boils down to fair use and open source claims against copyright and rights of ownership.

New York Times

One of the big players leading a push on copyright issues with ChatGPT is the New York Times. They launched a lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft in December 2023. It would be fair to say that this has resulted in a particularly acrimonious dispute.

The lawsuit (covered for example here and the original complaint is available as a PDF here) alleged that millions of New York Times articles have been used to train the ChatGPT models, and that as a result ChatGPT could generate content verbatim, even when that content was locked behind a paywall (i.e. only available with a subscription).

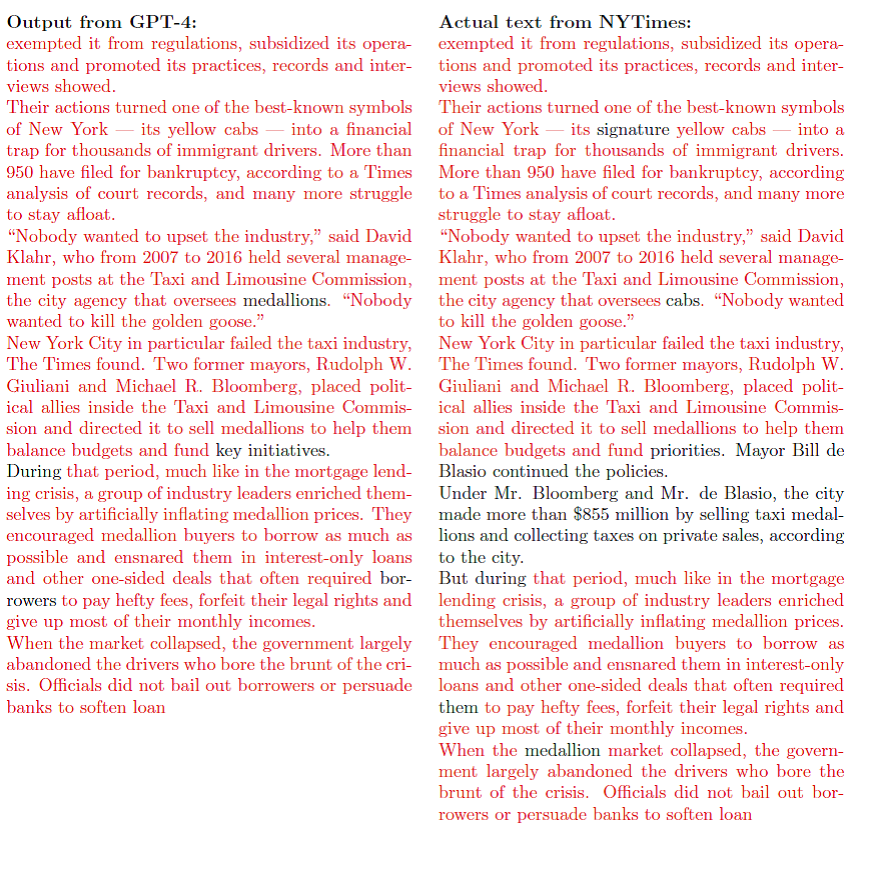

One example relates to a Pulitzer-prize winning series relating to New York’s taxis. The New York Times claim “OpenAI had no role in the creation of this content, yet with minimal prompting, will recite large portions of it verbatim” and provide the below example image comparing the original content with content from ChatGPT, matching content is highlighted in red:

There are numerous similar examples which can be found in the complaint itself.

In response, OpenAI claimed that “The truth, which will come out in the course of this case, is that the Times paid someone to hack OpenAI’s products”. OpenAI claimed that it took tens of thousands of prompts to generate the “highly anomalous results” which the New York Times used to make their case. OpenAI explained that “Normal people do not use OpenAI’s products in this way”.

Another battle in the case concerns the New York Times accusing OpenAI of deleting data, including information gathered by the New York Times team when reviewing (for over 150 person-hours) a set of training data under an agreed inspection protocol, as well as deleting programs and search result data.

In a further interesting move, the New York Times published an article with a former OpenAI researcher who had decided to leave the company, apparently due to concerns regarding the approach to copyrighted material. The New York Times article states:

“The technology violates the law, Mr. Balaji argued, because in many cases it directly competes with the copyrighted works it learned from.”

A Big Moment?

In a separate, but similar case against OpenAI in California, a group of content creators sought the content of one of the training sets which was used to build GPT4. Reportedly, earlier this week Judge Robert M. Illman decided that the data should be provided.

This is not the first training data to be provided (see for example this article regarding the same case), but the data set is claimed to be highly relevant. Based on the reporting from Bloomberg, the data set “contains a number of web pages that ‘very likely’ contain copyrighted content owed by the author plaintiffs, the authors said in a filing on Jan 17”.

The provision of this training set could set a significant precedent for other intellectual property cases against Generative AI companies,

This data will likely be made available under the same provisions as prior training data (discussed in the Register article). However, if such data was to leak (above provisions not withstanding), then this could potentially expose further authors whose content has been utilised for training purposes.

Timing and DeepSeek

The timing of the decision is interesting because of the news this week regarding DeepSeek.

DeepSeek is a competitor to ChatGPT originating in China, recently exploding onto the AI scene and hitting the top of Apples App Store charts, despite apparently having been developed with a budget which is a fraction of that of OpenAI.

The release of DeepSeek has seen some resistance, with many raising concerns regarding data privacy, especially given that the terms and conditions reportedly allow for indefinite retention of any data given to it, which would be stored in China, under Chinese law.

OpenAI have reacted bullishly, and have alleged (in an article in the Financial Times) that DeepSeek is based on their content, suggesting that DeepSeek may have used a method known as “distillation” to build their model. Effectively this is where developers use a larger model (such as GPT4) to train a smaller independent model (like DeepSeek). OpenAI claim that this would be a breach of their terms of use.

OpenAI are effectively claiming that their content has been used by someone else to build an AI model without their permission. The irony has not been lost on many people commenting on social media.

There is evidence to back up OpenAI’s suggestions. DeepSeek does itself appear to think that it is ChatGPT (see for example this Reddit thread), and when asked for API information (Application Programming Interface – a method of communicating with the DeepSeek application from other programs), provides details of OpenAI’s API.

Not Just OpenAI

Returning to the copyright disputes, it is certainly not just OpenAI that are facing potential legal hot water with AI intellectual property claims. Getty Images are suing Stable Diffusion for using their images to build their models. Microsoft (in addition to being named in some of the OpenAI cases) are also being sued as a result of issues with their CoPilot tool within GitHub.

The issue within GitHub is that rather than generating new code, in some cases it appears to produce chunks of code verbatim from some projects. This could potentially be in breach of the terms on which the code was made available.

In the GitHub case, lawyer Matthew Butterick said that “We’re in the Napster-era of generative AI”. The future of the California case may decide if ChatGPT meets the same fate as the infamous music sharing site.

Going Forward – UK Government

I have commented on this before, but the UK Government recently proposed allowing tech firms use copyrighted material to train models. There would (in theory) be some ability for creatives to “opt out” of this process. Quite how this would work is unclear and as you may expect, creative groups have come out against the suggestion. This could be a fascinating area to monitor going forward.

An Interesting Analogy

I remember when I was a student I had to go and find details and content from books in the library. During my PhD this was often research articles in published journals etc. Many of those journals could not leave the library, so if we wanted any content to work on from home, we would have to photocopy the content.

There are exceptions in copyright law and additional licensing that allows for some copying of content for educational purposes. These exceptions are still limited.

There were large signs everywhere around the photocopiers explaining that copyright law limited what we were allowed to copy and that we could be prosecuted for taking more photocopies than we were legally entitled to.

Based on this article from the University of Bath (https://www.bath.ac.uk/guides/understanding-copyright-and-keeping-your-copying-legal/), currently you would be allowed 5% of a work, or one chapter, or a single article from a journal (a problem if there are two articles you need to study from the same journal edition). For teachers and academic staff the limits appears to increase to 10%.

Given that OpenAI appear to be able to provide access to training material used to train their models (see above discussion on the review of training sets), they must have generated a copy of that data scraped from the internet. This would suggest that OpenAI are copying this content in full, something that a student would not be able to do (legally).

If the UK Governments suggestion was implemented, you would be able to copy the entirety of a copyrighted work to teach a machine, but not a student.

Warning – Using ChatGPT to Create Content

A point that I wanted to conclude on is in relation to the use of Generative AI to write content. I have raised in some of my presentations that there are risks to using generative AI to write content itself. I recommend using it as a supporting tool, for example to create lists of content to include in an article on a topic, or to make sure that you have not missed anything. If you use generative AI to write the actual content itself, then firstly, it may not sound great. Generated articles can often come across as very flat and it can be possible to identify content that has been automated. The other risk is with regard to plagiarism.

When you use generative AI to write content, you do not know where that content has come from. Given that it has been demonstrated that it is possible for content to be provided verbatim from copyrighted material, it follows that any content could be provided verbatim in a response. This means that your post about Artificial General Intelligence that you had ChatGPT write, could turn out to be plagiarising someone else’s content. This could cause you serious issues, and may be a sign of further potential intellectual property legal cases involving generative AI in the future. It could also lead to a potential approach in defence of cases (“I didn’t plagiarise your work, I used generative AI”). If that is any better, I will let you decide.